Personality assessments are a big thing in leadership, and I have to admit that I’m quite torn on what I think of them. They can be incredibly useful, but they can also be widely misunderstood: used more as a “leadership blood test”, if you will, as a diagnostic tool, than a personal weather forecast.

Like me, you will no doubt have met the person, the team or, in rare cases, the business which has gone all in on a specific tool. Compulsory four letter word combos in email signatures, meeting agendas accompanied by a list of Strengths for each person attending, or even a ring of DISC-inspired colour around Teams profile pictures.

Many of these tools aren’t fully scientifically validated, although they all to some extent borrow liberally from psychology, and almost all of them end up being used really confidently. Even if they’ve been introduced in a really responsible way.

It speaks to the human desire to understand

As a leader, I like to be driven by the data and the facts. Rather making my point that these measures are in fact useful despite their flaws, that’s something that my number 5 strength from StrengthsFinder(R) “analytical” explains about me.

And it’s that “oh, that sounds familiar” element to all of these metrics that lend them to exactly what we quite like as humans, and – therefore – as leaders. They, with some basis in science and enough basis in reflecting some elements of reality about us to ourselves and those who interact with us, turn the complexities of personality into something simpler. They help us to understand more about one another and ourselves by creating structure out of the very unstructured.

Is it true? Well yes. And no. Probably. It really is hard to say – and hard to resist.

It’s a starting point

Used well, personality assessments create conversations that wouldn’t otherwise happen because commenting on someone’s personality is either rude, or incredibly hard, or both. So these tools give us formulated ways to create neutral conversations about how people are different, without judgement. They help people recognise patterns in how people might respond in different situations.

Some show us strengths and encourage us to lean into them, acknowledging but also accepting those areas where we’re less strong: a valid way of looking at things, albeit one that doesn’t work too for those of us – me – who like to focus on seeing problems and finding ways to fix them, to make even a good thing better.

Some of them, on the other hand, create natural starting points from which we can plan self development plans or programmes for people, removing the situation from the action to help us be clearer about how certain situations tend to result in certain ways of thinking and certain ways of doing, and how we might use that knowledge to improve how we interact at work to improve outcomes.

Crucially, they can also build empathy — not by explaining who someone is, but by suggesting why they might approach things differently and tolerance, by explaining that sometimes you have to adapt your ways to others (or, even better, try and meet in the middle).

So treat them for what they are: a starting point, not a conclusion. A lens, not a verdict. A personal long-range weather forecast.

A helping hand to see gaps you can’t

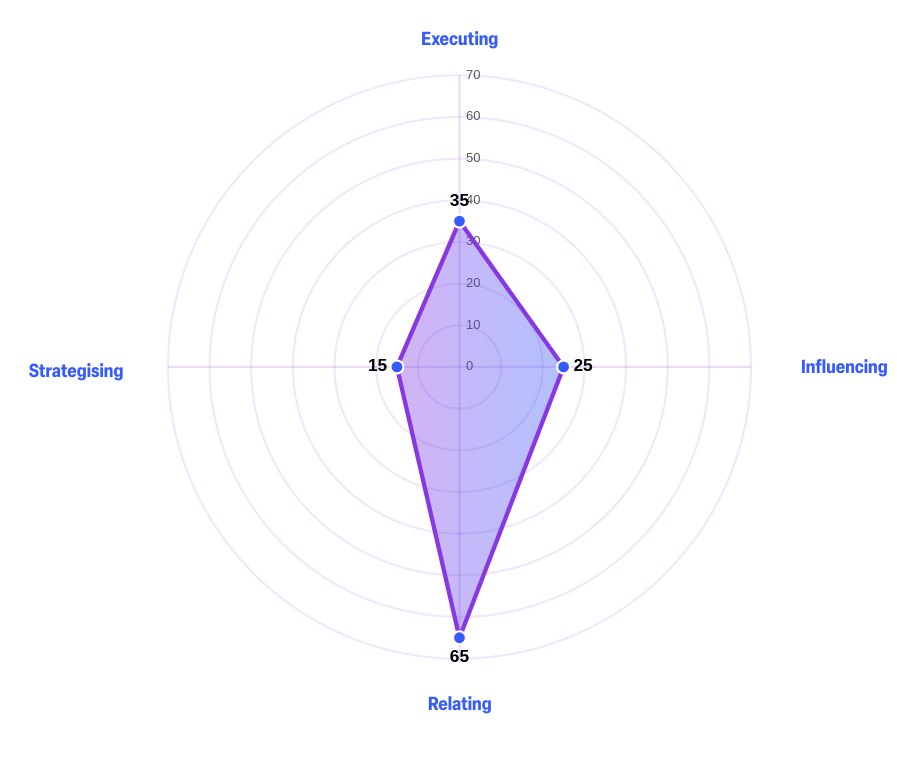

As well as helping you spot where you might focus development yourself or with a team member or mentee, I’ve also found good use for tools – in this case, Gallup’s StrengthsFinder – as a really effective way of mapping a team, finding blind spots and helping with making sure my team is not too samey.

My team – a few years ago now – was having trouble hitting deadlines. Every project seemed to be delayed for one reason or another, and things had got worse as we’d gone on that journey all in-house marketing teams must go on from reactive administration into strategic function. What was happening? Why was it happening? I was not entirely sure.

Mapping StrengthsFinder across the team gave us a starting point. The strengths of the team were significantly biased towards relating skills. As we’d moved away from being reactive, a customer-service type operation, things had stalled because the team was stronger at building relationships than they were at anything else.

A really helpful starting point. But also, a really easily misinterpreted one. Because my team were also fantastic at getting stuff done, churning out more work than you’d think from the number of people there – until someone else, perhaps someone else who wasn’t fully on board, got involved. And then it had a tendency to stall.

A fantastic insight – I felt relieved at the time to finally have a starting point to work from – and one we were able to overcome, in part by ensuing the next opportunity we had we were recruiting people with strengths in other areas to help us achieve a better balance, and in part by identifying and understanding the gap we had as a team so we could deploy the right people to the right projects. And I supported the individuals involved with coaching and development, so they had a full understanding of their strengths and found ways to understand and use what StrengthsFinder had told us to develop.

Living up to them

And that’s the crucial point for me.

My concern starts to come when something one of these assessments has told us turns into either something to lean into, or something to which we find ourselves quite attracted. Phrases like “Oh, don’t mind me I’m a HBGD, I always do this” concern me not because – perhaps – the statement is true (I’m more than happy to work with people however they want to work, I love variety and new perspectives), but because it starts to get in the way of the person, and of their development.

If these personality assessment tools are a starting point, it cannot also be the finishing point. Used badly, they flatten people. They over-simplify complexity. They replace curiosity with certainty. They replace a prompt for development with – dare I say it – an excuse to stay as you are.

And that doesn’t help anyone, does it?